Sign up to our newsletter

Subscribe to our mailing list to get the latest insights, news and market updates delivered direct to your inbox.

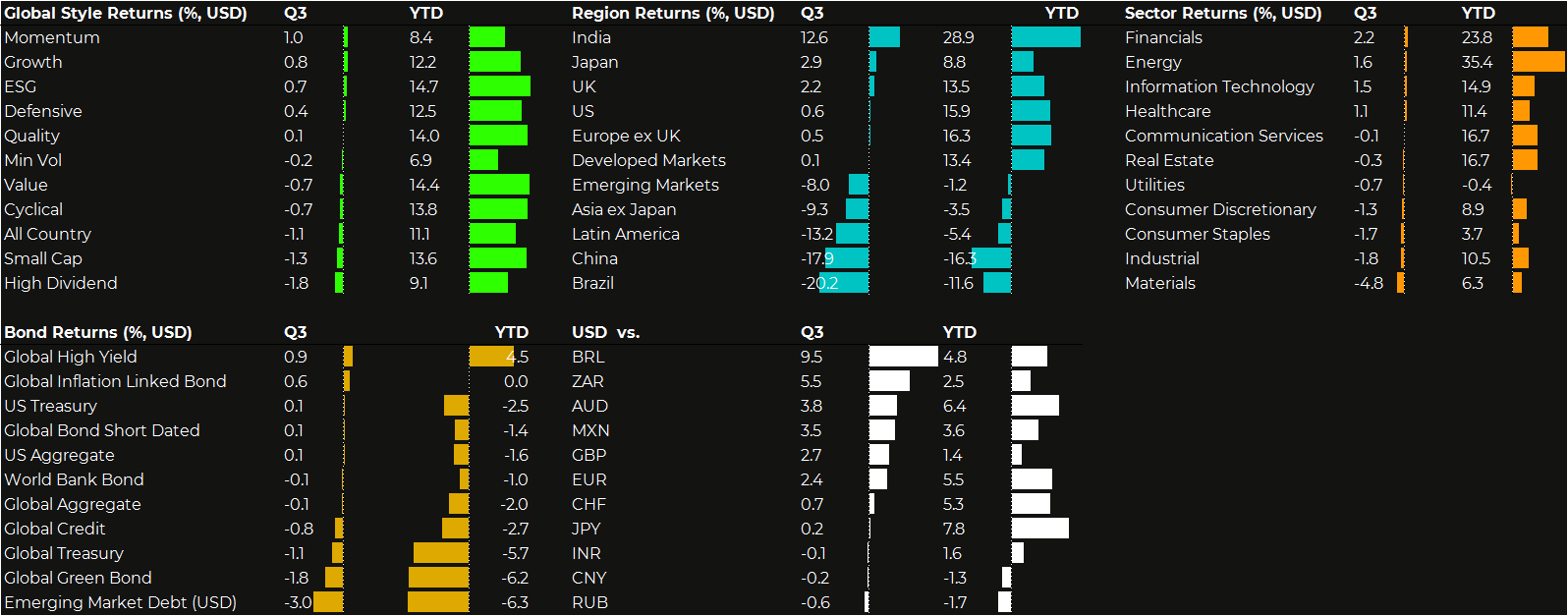

After stock markets marched higher in the first half of 2021, we wondered if that progress would be tested, as policymakers moved closer to ending emergency support. The quarter began well for equities, with indices making new record highs. But recent weeks have seen a little turbulence erase those gains, undermined by concerns over central bank policy, rising bond yields, developments in China, and the growth outlook. Global equities ultimately gained just 0.1% in Q3 (in US Dollar terms).

Japan and the UK led in the third quarter; Japanese stocks gained 3%, on hopes that a new Prime Minister would introduce supportive fiscal policy, and UK stocks gained 2%, despite concerns about local supply shortages. Weaker Sterling and comparatively cheap valuations were helpful; UK companies are at the forefront of international buyers’ minds, with very robust inbound M&A.

Emerging market equities lost 8% for the quarter, largely due to China. Chinese stocks fell 18%, undermined by regulatory interference in the education and technology sectors then by the looming default of a leading property developer. Brazilian equities lost 20%, exacerbated by currency weakness, hit by weakening Chinese demand for iron ore. Brighter spots in emerging markets were India (+12.6%, lifted by improving corporate earnings) and Russia, up 10% on rising oil prices.

After the sharp divergences of recent quarters, there was less to choose between Growth and Value styles: global growth stocks strengthened slightly (+0.8%), global value weakened (-0.7%). The valuation premium for Growth stocks over Value stocks remains around record levels.

At the sector level, Financial stocks outperformed (+2.2%, helped by yield curve steepening) and Energy companies added slightly (+1.6%) to their stellar gains of recent quarters; Energy has now gained over 70% in twelve months. There were modest falls in Q3 for Staples, Consumer Discretionary and Industrial stocks, but Materials saw a sharper fall, down almost 5%.

Given the series of challenges markets have faced, after such a strong run higher in equities, a flat quarter looks like a very resilient performance. Driven by good news on vaccination and booming consumption as Covid restrictions eased, markets initially delivered an unusually strong summer rally, with the S&P 500 notching up 28 new record highs, before the winds changed. September’s fall may have erased most of the quarter’s gains, but year-to-date gains remain strong and the drawdown as at quarter end was quite modest: global equities fell just over 4% in USD terms in September (although they extended that loss in the early days of Q4). For Sterling-based investors, the weakness of the Pound helped offset the September loss: in Sterling terms, global stocks fell just over 2% in September, and delivered a small positive return for the quarter as a whole.

Global bonds also returned 0.1% in Q3. Yields initially fell in July on concerns over the Delta variant and a slight fading of inflation worries, before rebounding. The yield on benchmark US 10-yr Treasuries finished the quarter barely changed at 1.49%, but yields on shorter duration bonds nudged higher over the quarter as markets became more confident about the Fed’s path towards tapering – the gradual removal of emergency QE.

High Yield bonds returned 1%, with a slight widening in credit spreads offsetting decent income generation. At this stage in the credit cycle, the big recovery gains have been made in credit, and investors are more reliant on “coupon clipping”. Inflation-linked bonds outperformed again: US TIPS and UK Linkers gained around 2%, with investors seemingly still ready to buy costly medium-term inflation protection. Gilts lost almost 2%, with yields rising sharply to 1% (the highest since mid 2019), as the Bank of England indicated rates would rise in early 2022. Emerging market bonds suffered, particularly local currency bonds, where the widespread weakness of EM currencies against the Dollar was a headwind.

As the risk-off tone prevailed in September, the US Dollar strengthened, rising around 2% against the Euro bloc in Q3 and a little more against Sterling. The UK is suffering more than most under supply and distribution constraints, with labour shortages in key industries, gaps in supermarket shelves and queues at filling stations. However, the Bank of England’s move towards higher interest rates perhaps prevented a bigger fall for Sterling.

Commodities saw some extreme price action, especially Energy, where the combination of recovering demand and low inventories squeezed prices sharply higher. Oil has traded up to around $80/barrel (over a 50% gain YTD), refined products like heating oil and gasoline saw stronger gains, and Natural Gas rose over 50% in Q3 alone, reaching its highest prices for a decade. Even sharper moves have been seen in local energy markets, particularly the UK, where supply chains have been impacted hard by Brexit-related disruption in labour markets, and limited storage capacity.

Energy price rises can have far-reaching implications. Investors are primed for inflation from higher fuel prices, with firms trying to pass on higher costs – often successfully. However, users often cannot respond to rising energy costs by cutting consumption. This means price increases can act like a tax, cutting discretionary spending power, dragging down profits across a swathe of sectors, and ultimately dampening the growth outlook: inflationary short-term, but potentially deflationary in the medium-term. If higher energy prices persist, economists may be forced to trim growth forecasts.

Gold has remained rangebound, trading well below its summer 2020 highs. Bitcoin remains extremely volatile, providing opportunities for traders to win or lose significantly, a problematic feature in what some view as an alternative store of value. It ended the quarter around $48,000, up over 30% in the quarter, but still well below its springtime highs.

The first half of 2021 was about inflation concerns, alongside optimism about booming growth, as vaccines allowed ever more economic reopening. This picture has recently become more complicated, with investor concerns shifting towards the growth outlook.

Markets largely digested inflation risk earlier in the year, concluding that temporary supply constraints and sudden shifts in patterns of demand were causing price surges in some sectors, for example in used cars and air tickets, but that these could be transient. However, supply bottlenecks are now affecting the growth outlook, not just inflation, and markets’ attention has zoomed in on this aspect. Global surveys of firms indicate that shortages of materials and components are holding back output across multiple industries, delaying deliveries and in turn starting to undermine manufacturers’ demand for labour: if you can’t get hold of a vital part, you can’t make the finished product, and you don’t need staff on the idle production line.

There is not yet a major problem with consumer demand; on the contrary, consumers seem prepared to spend the savings accumulated during lockdown, releasing pent-up demand as more economies open up. The problem lies in firms’ ability to meet that demand. Reopening may push a rebalancing towards spending on services – travel, leisure, entertainment – but here too businesses report various constraints, from lack of staff to shortages of ingredients. Where services companies are struggling to find the right staff to meet demand, this results in lower than expected jobs growth and higher than expected wage growth: for some, this carries a whiff of stagflation, a potentially toxic mix of slowing growth alongside high inflation. Adding the effects of rapidly rising energy prices to this picture hardly helps.

The critical question for investors is how policymakers will navigate this shifting picture. It is increasingly apparent that central banks are moving away from emergency policy support. Interest rates may remain very accommodative for some time yet, but policymakers have confirmed that QE bond purchases will be tapered, or reined in, and the first interest rate rises are coming into view. The Bank of England is now widely expected to start hiking rates early in 2022, the Fed later in 2022. It was always clear that markets would need to digest this tapering, and policymakers have trodden very carefully to make this process as painless as possible so far.

If supply constraints are seen to be a temporary but surmountable speedbump for growth, the implications may not be too serious; but if signs of stagflation become stronger, there’s a risk of a central bank policy error and a much more turbulent market environment.

With investors’ focus on the growth outlook, political developments may be slightly in the background. I am writing from Berlin, where negotiations continue after the German elections. The impending departure of Chancellor Merkel marks the end of an era, and coalition mathematics point to a centre-left administration of SPD, Greens and FDP (liberals) – an outcome unlikely to ruffle investors. Japan faces another election in November, after the short-lived Suga premiership: investors hope a new prime minister will herald new economic stimulus. In the US, we ended the quarter with the $1tn+ infrastructure stimulus bill still making painfully slow progress through Congress, while Biden promises it will get over the finish line.

The latest Covid-19 wave appears to be abating in much of the world, as vaccine take-up spreads: over 3 billion doses were administered globally in Q3, more than the preceding six months. Slower starters, like Brazil, Japan and China, have made stunning progress recently – China is now one of the most-vaccinated countries on Earth. As a result, new infections are falling globally (around 400,000 daily new cases, compared to 700,000 in August), but areas of serious concern remain, especially the US, which now accounts for about a third of global daily virus cases and deaths, with around 2,000 deaths a day. So far this is having limited effect on the reopening of the economy, but the possibility of some restrictions being reimposed should not be dismissed.

It’s not hard to spin a threatening story for equities. Stocks have rallied explosively over the last year or so, setting new records, and equity valuations are high, especially for growth stocks. Bond yields have risen – perhaps not far enough yet to significantly undermine equities, but further rises could take us to that point. Regulatory and credit risks in China seem significant, energy prices are rising and Covid-19 has not gone away. A potential loss of growth momentum while inflation remains stubbornly high would create a major dilemma for policymakers: can they continue to withdraw emergency policy without triggering market turbulence or undermining the growth outlook? Or will they be forced to change tack, stoking inflation concerns?

Some investors paint a more positive market picture. Corporate profits have been growing strongly, often beating forecasts, supply shortages and bottlenecks will be resolved (in part through higher capital spending, which may underpin future economic growth and productivity), household balance sheets overall are in pretty good shape after a period of unusually high saving, and consumers have the means and the desire to spend after the constraints of the last eighteen months. And even with a gradual tapering of emergency policy support, central banks are still operating with a very pro-growth stance.

The tension between bulls and bears makes a market, but with plenty of ammunition for both sides, bouts of market turbulence would be no surprise. Thoughtful and robust portfolio construction remains as important as ever.

N.b. All content is based on data at the time of writing on 8 October 2021.

Subscribe to our mailing list to get the latest insights, news and market updates delivered direct to your inbox.